2020–23

Title: Mudan ting – Ein Gespenst geht um in China

Instrumentation: Fully staged large-scale opera

Year: 2020–23

Duration: approx. 2 hours

Premiere: Mannheim Nationaltheater 2027

Performers: Mannheim Nationaltheater

Mudan ting – Ein Gespenst geht um in China

Reinventing opera in the 21st century

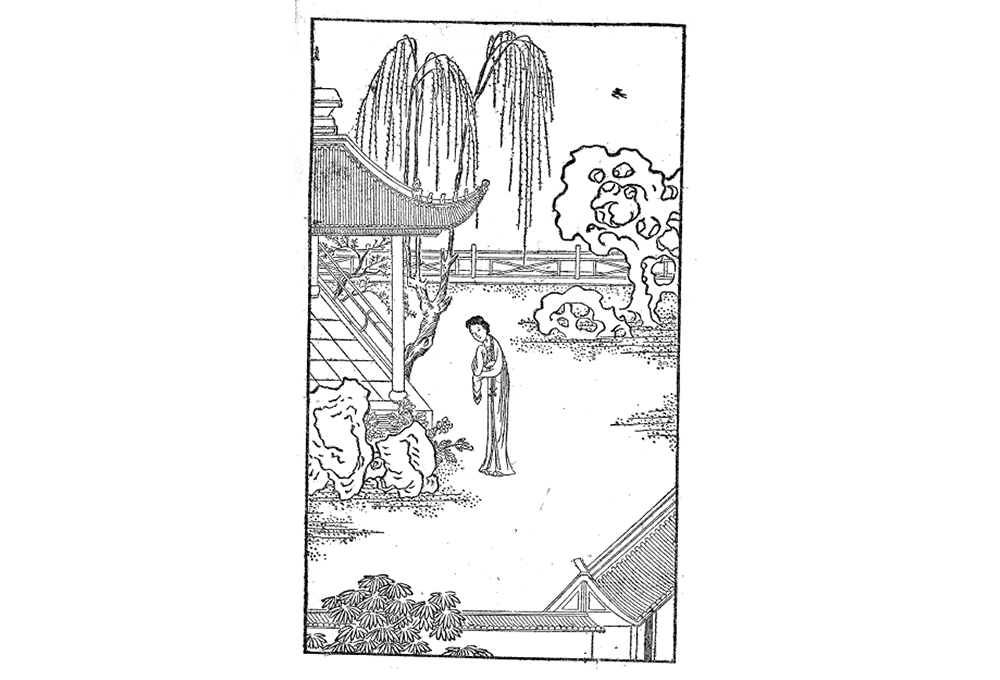

Mudan ting (The Peony Pavilion) is a Chinese ghost story. The beautiful Du Liniang dreams of her lover, the young scholar Liu Mengmei, and dies when her love is fulfilled only within the world of dreams. Her ghost returns to earth to find the real Liu Mengmei so that she and the young scholar can consummate their love for one another. Author Tang Xianzu wrote Mudan ting in the later Ming Dynasty in 1598. The complexity of his writing and the status he holds in Chinese literature has many parallels to another contemporaneous author in the Western world, William Shakespeare. Both authors died in 1616. When Tang Xianzu wrote Mudan ting, Shakespeare was composing his sonnets and eventually, in 1611, wrote The Tempest as reports of the new world were being circulated throughout England. It was around the time of The Tempest, in 1619, that the first import of African slaves became the economic backbone for what would become the United States.

Many ghosts find their medium through Du Liniang and return to haunt the world with the violence they enact. In this reworking of Mudan ting, the figure of Du Liniang becomes synonymous with the year 1937, a year in which ghosts from the turn of the 17th century and ancient China are brought into a rushing vortex with those spirits that continue to terrorize us from the early 20th and turn of the 21st centuries.

In 1937, Vincenz Hundhausen, a professor in German literature based in Beijing, completed a German translation of Mudan ting. In the same year, the Nazis terminated Hundhausen’s position in the university, as his work was not suitable for the new political era in Germany under National Socialism. It was during this time that the poet Paul Celan began translating Shakespeare’s sonnets and, in 1941 during his months in forced labor under the Romanians and German Einsatzkommandos, produced his translation of Sonnet 54 (“O how much more doth beauty beauteous seem”).

In 1937, the Chinese Communist Party was on the rise as Mao Zedong penned the important essays “On Contradiction” and “On Practice”. By this time, Mao had influenced Bertolt Brecht, as Brecht in 1937 revised his Lehrstück (teaching play) Die Maßnahme, which was set in China. After the war, Brecht specifically used Mao’s essay “On Contradiction” to teach actors how to interpret Shakespeare’s Coriolanus by focusing on dominant and secondary contradictions within the text.

The ghosts returned in 1978 when China, under Deng Xiaoping, opened their doors to the economic policies of the West that had previously been disallowed under Maoist rule and, in the race to catch up with the West, created ghost cities seemingly built for no-one in a display of modernization and urban development. Under China’s rapid economic growth, a ruthless free market system with no regulation or safety standards produced irreconcilable social inequalities. A strange marriage between capitalism and state authoritarianism seemed inevitable for China to develop as the world superpower in the 21st century against the twilight economies of the United States and Europe. This relationship holds eerie similarities to the marriage in Mudan ting between the scholar turned grave robber Liu Mengmei and the resurrected, dead body of Du Liniang.

By returning to earth, Du Liniang’s quest to consummate her love becomes one of reversing time, of reconciling with Liu Mengmei when their forms of representation – as human and ghost, the living and the dead – are irreconcilable. This is an opera in which various means of magic spells to reverse time – reversible poems and star maps, anagrams, puzzle and mensuration canons, retrograde musical structures, irrational time-measures, serial incantations and polytemporal constellations – are brought to bear on events that are fundamentally irreversible such as rape, suicide, violence and torture.

The ghosts can be found appearing as early as 81 BCE when the Confucianists debated the Legalists as to the role a State should provide in the regulation of economic practices, in this case the commerce of salt and iron. The State, under Emperor Wu, intervened by creating monopolies on China’s salt and iron enterprises, price stabilization schemes, and taxes on capital, in order to pay for the government’s brutal military and colonization campaigns in the north and west.

So many ghosts. When Tang Xianzu completed Mudan ting and Shakespeare The Tempest, the economics of slavery slowly lay the foundation for post-war American capitalism when neoliberal economic policies were put into place. These policies championed austerity in parallel with deregulation, privatization, trade and financial liberalization, lower taxes, and small government. It was during this period that the Middle East became central to the United States’ global strategy to maintain control of Western Europe and its rivalry with its two main competitors, the Russian Federation and China. Developing crises due to these economic policies exposed the United States to instability in its global position, which it countered by invading and destabilizing Middle Eastern states. The 2003 invasion of Iraq was central for the United States to dominate global capitalism after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Beginning in 1937 and published in 1940 was Ezra Pound’s “China Cantos”. In this work, Pound reinterprets Chinese history in order to support his own views for strong State leadership to address 20th century fiscal and cultural problems, which partly explains his support of Mussolini. His earlier misunderstanding of the Chinese language in his Cathay translations of Chinese poetry, largely through the notes of Ernest Fenollosa, gave rise to the Imagist Movement in poetry, in which values of modernism are brought in relation to the rise of 20th century capitalism and the violence that such economic policies enacted. The violence of the Cathay translations is a glimpse of a much larger relationship between language and war.

Translation of the Chinese language – as Pound and Hundhausen had practiced it – became a form of colonization, where identity is fixed with a solidification of signifier and signified, in order to build a familiar (and powerless) image of China and “the East”. The promotion of a social consciousness with clear representation of “otherness” happens mostly through the medium of language, by which language becomes complicit in the acts of violence that invariably emerge. The grammar of language, in particular, can create and manipulate connections between events in order to participate in the development of a war program before hostilities, so that methods of violence, rape and torture can be justified.

Most importantly, 1937 marks one of the most egregious acts in Chinese history, the Nanjing Massacre, when the Japanese murdered over 300,000 Chinese along with committing acts of widespread rape, an event that even the staunch Nazi Party member John Rabe described as too horrific. But the 300,000 Chinese were just a small part of the 3.9 million Chinese that were killed under Japanese operations in China during this time. In 1937 Brecht’s friend Mei Lanfang, who was famous for his portrayal of Du Liniang in Mudan ting, refused to sing for the Japanese.

The dead return among the living and continue to haunt us. This is an opera that attempts to speak to who we are at this present moment when unprecedented acts of political, social and environmental self–harm are causing racism, xenophobia and its violent effects to be on the rise. It is an opera that has everything to do with geology as the study of that which is not visible, or barely so. This opera gathers that which is underneath us, in order to gain awareness of the material and cultural forces that pass through these stratified layers of accumulated earth so we awaken to what cannot be buried.